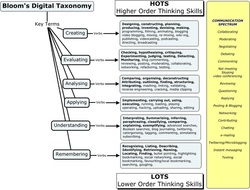

Bloom's Digital Taxonomy Concept map (Revised by Andrew Churches)

Bloom's Digital Taxonomy Concept map (Revised by Andrew Churches) Inspired by relatively recent developments in Adult Education in Greece (2005 - ) and by ICT applications available for teaching purposes in the digital world, I decide to present a historic continuation of representative learning theories in this field. As TEFL/TESOL Adult educator and former member of Internal Evaluation team (Adult Education Centres, Body of Regional Evaluators and Quality Assurance Auditors of Lifelong Adult Training and Education Services, 2007-2008), I will attempt to make reference to indicative points by outlining each theory as briefly as possible in the hope that my friends and colleagues will have an overview of the overall ‘evolution’ of Life-Long Learning and Adult Education and will better understand their own methodological choices.

A. Socratic seminars

As pointed out in the e-material on Adult Educators’ training course (General Secretariat for Adult Education, Greece, http://www.keeenap.gr/lms/ 2007-2008, ), Socrates (470/469-399 BC), Greek philosopher and figurehead of central themes in Western philosophy, used dialectic discourse in instructor-directed form in which rhetorical questions were employed as a teaching approach to elicit ideas and not to ethically moralise or spoon-feed. His ultimate aim while associating with people of all social classes was to lead the learner to global truth and knowledge of ethical values by activating their inner self-know and critical reflection in search of wisdom and prudence. Through his use of ‘maeeftiki’ (/mεεftικί/ Greek for Midwifery, Obstetrics), metaphorically used to indicate the process of helping bring ideas to life, Socrates is distinctive for the development of the Inductive Method of reasoning – Rationalism. His teaching method is problem-centred, based on self-discovery, elicitation, critical thinking and on the initial assumption that ‘I know one thing that I know nothing’.

Students are engaged through the realisation of ignorance (aporia and elenchus) and are prepared to actively pursue new knowledge. Understanding and compassion for learner educational needs and group expectations prevents this method from appearing as a strict questioning exercise.

It is still well accepted by a good number of adult learners, according to recent research in Vocational Training carried out by Paraskevas and Wickens (2005), and surely you can recognise some of its key elements, highlighted with colour here, as part of your own TEFL/TESOL lessons.

Parallelism with staged lessons and transition from new language to freer practice and integration may be viable here.

B. Knowles’ Andragogy

The “art and science of helping adults learn” developed at the end of the 60s until the end of 80s and was introduced with the term ‘Andragogy’ by American Educator Malcolm Knowles (1913-1997). This theory refers to adult learners’ need for self-recognition and realisation of their own full potential. By 1984, Knowles’ Andragogy is a process model as opposed to ‘Pedagogy’ which is a content model with behaviourist elements. It differentiates adult learners from children/teenagers by attributing different characteristics to each age group, which calls for a different type of education. Although this distinction is not necessarily lucid (Rogers on definition of self, 2004 & Kegan in Mezirow, 2007), Andragogy is based on adult needs for self-directed learning through which they can accomplish self development by own initiative. The educator’s main role according to this theory is to act as facilitator in the learning process (Kokkos, 2005) through choice of methods to activate and promote learner – educator interaction. For Knowles, Andragogy is initially based on four crucial acceptances (1998): 1. Self concept, 2. Experience, 3. Readiness to learn, 4. Orientation to learn, 5. (added later on) Motivation to learn.

Allen Tough suggests that, in order for self-directed learning to take place, change should happen for educators who should pursue educational development for themselves first and should offer their learners more options in the learning context. Although it has been claimed that the theory of Andragogy is not sufficiently grounded by research and is more of an ideological and humanistic consideration of adult education (Brookfield 1986, Jarvis 1985, 2004), it still offers useful insight in teaching and works best when considering the uniqueness of learners and their learning contexts.

Are you involved in investigating your learners’ educational needs, knowledge, skills, interests and aspirations at an effort to tackle or prevent learner anxiety and negative feelings? Are your TEFL/TESOL adult learners oriented towards solving problems, making choices, pursuing successful learning, synthesising ideas about learning and developing their own thinking? Then, perhaps, it is this autonomy that will help you construct a ‘learning contract’ with your class, link course aims with learner expectations and also prevent possible dropouts from the learning team.

C. Freire’s Education for Social Change

Influenced by his work to combat illiteracy and to empower socially secluded groups in Brazil of 60s, American Paulo Freire (1921–1997) encouraged collective action leading towards social change. According to Freire, the use of dialogue based on respect, love and tolerance (free of subjective bias) has a pivotal role in promoting parity and is treated as indicative of respect for dignity and freedom.

The aim of learning, as stated by Freire, is to lead the adult learner to emancipation and therefore change (in Kokkos, 2005). Through completion of the three stages of this theory, Investigative-Thematisation- Problematisation, the learner is in the position to achieve awareness that their opinion and position in the world are formed by social and historic forces (Freire 1972).

Because of this positioning that no education is neutral, Freire’s theory may be viewed as a political rather than as yet another educational approach to adult teaching (Jarvis, 2004).

With particular reference to socially vulnerable groups of learners, the adult ELT educator needs to investigate the learners’ educational needs through use of dialogue based around learner problems. Encouragement of respect, acceptance, love, enhancement of self-esteem, creating equal opportunities for active participation, understanding of background experiences, exchange of opinions are all key areas of this theory to strengthen group dynamics and bring change to attitude until completion of the course.

Of course, it is up to the individual educator to determine the extent to which the model of Social Change serves their teaching context, their current circumstances and demands on the basis of their aims, group profile, teaching framework and objectives on the course (e.g. General English, Academic English, Vocational Training, Continuing Education), but is there a single professional out there who does not pursue customer satisfaction?

C. Mezirow’s Transformative Learning

Jack Mezirow (1923 - ), American scholar, figurehead of Transformative Learning theory, stresses that the adult educator’s role is to support learners towards re-examination of dysfunctional beliefs, practices or false ideas. This psychological approach to adult learning developed by Mezirow in 1978 inspired many in the women's movement and focuses on deep changes in how adults see themselves and their world (Mezirow, 2000). According to Mezirow, there are three types of learning, Instrumental (aiming at problem solving), Communicative (aiming at comprehension) and Emancipatory (aiming at questioning ideas in the process of critical reflection).

In order to help develop autonomous thinking, learners are not involved in mere accumulation of ideas and new knowledge. Instead, they are encouraged to transform their taken-for-granted frames of reference (meaning perspectives, habits of mind, mind-sets) (Mezirow, 2000) through a 10-step process involving:

1. a disorienting dilemma

2. self examination

3. critical evaluation of convictions

4. recognition, analysis and sharing of experiences and transformational process

5. assuming new roles and building competence

6. planning, action plan

7. acquiring knowledge and skills to materialize the action plan

8. trying new roles and assess feedback

9. building self confidence and new skills

10. reintegrating into society with a new perspective

All this can be achieved through learner-centred activities that break the ice (e.g. role plays, ‘alter ego’, ‘snowballing’, simulations, group work), which lend themselves more easily in a language class, to create a secure atmosphere and to promote self-know, exchange of ideas, rational thinking, critical reflection, expression of feelings and elimination of fossilized insecurities.

The role of the educator is not to dogmatically influence adult learners but to allow them the freedom to specify their aims, roles, expectations and ways of assessment. This theory of learning is based on the belief that human tendency to perfection is manifested through improvement of awareness and through the quality of our actions within a meaningful learning process (Mezirow, 2007).

D. Bloom’s Taxonomy – Revised and Digital

In order to promote and better understand student learning, Bloom (1913-1999) supports that it is important to classify thinking behaviours (Bloom and Krathwohl, 1956). He identifies three domains of learning, Cognitive (Knowledge), Affective (Attitude) and Psychomotor (Skills), which provides the basis for ideas used by academics, teachers, educators and trainers. This taxonomy is primarily created for academic educational purposes but applies to all types of learning and focuses on improving the effectiveness of developing mastery instead of simply transferring facts. In 1990s and 2001 former students Anderson and Krathwohl revise the six categories of Lower and Higher Order Thinking Skills.

Courau (2000) introduces the use of verbs for each level of educational aims and considers the use of the three levels of learning and their description of aims as necessary for any course and any teaching unit to fulfil its potential.

Andrew Churches (2008) recently updates the revised taxonomy to incorporate the latest developments in ICT applications. Based on the Taxonomy Elements, horizontal and vertical reference is made to the use of digital tools (from PowerPoint, WP and Movie maker to PLNs and YouTube) in order to promote learning with particular reference to the maths class.

Careful specification of aims determines course content and assists in selecting appropriate techniques and tools to use on any given course.

Application of the Taxonomy is not only applicable to teaching contexts but determines criteria for the selection of employees in a good number of State and Private sector institutions worldwide to sustain high quality of provision. Adhering to an Equal Opportunities Monitoring Scheme, these institutions shortlist candidates and appoint staff on the basis of Desirable and Essential Skills, Abilities and Competencies required. To provide high quality services, characteristics that distinguish levels of performance are considered, such as job-specific Knowledge & Skills, Quality, Professionalism & Accountability, Collaboration, Interpersonal skills & Teamwork, Commitment to Values, Management of self & Organisational skills.

For further reading, you can refer to the following

http://www.scribd.com/doc/8000050/Blooms-Digital-Taxonomy-v212

http://www.eduteka.org/TaxonomiaBloomDigital.php

Anderson, L.W., and D. Krathwohl (Eds.) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: a Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman, New York.

Bloom’s digital taxonomy http://edorigami.wikispaces.com/

Bloom’s revised taxonomy http://www.kurwongbss.eq.edu.au/thinking/Bloom/blooms.htm

Bloom, B. & Kratwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: Longman.

Brookfield, S. (1987).Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Churches, A. 2007, Educational Origami, Bloom's and ICT Tools http://edorigami.wikispaces.com/Bloom's+and+ICT+tools

Courau, S. (2000) Les outils d’excellence du formateur, ESF editeur

Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Freire, P. and Shor, I. (1987) A Pedagogy for Liberation. Dialogues on transforming education, London: Macmillan. 203 + xiii pages.

Jarvis P. (2004) Συνεχιζόμενη εκπαίδευση και κατάρτιση: Θεωρία και Πράξη, Μεταίχμιο, Αθήνα

Knowles, M. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. (2nd ed.) New York: Cambridge Books.

Kokkos, (2005) Adult Education: On tracing the Field, Metehmio Patras: Hellenic Open University (in Greek)

Κόκκος, Α. (2005) Εκπαίδευση Ενηλίκων: Ανιχνεύοντας το Πεδίο, Μεταίχμιο, Πάτρα: Ελληνικό Ανοικτό Πανεπιστήμιο

Kokkos, A. (2005) Educational Methods, Patras: Hellenic Open University (in Greek)

Κόκκος, Α. (2005) Εκπαιδευτικές Μέθοδοι, Πάτρα: Ελληνικό Ανοικτό Πανεπιστήμιο

Mezirow, J. (1990) Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Mezirow, J. and Associates (2007) Learning as Transformation:Critical perspectives on a theory in progress

Rogers, J. (1977) Adults Learning, Open University Press, Milton Keynes.

Tough, A. (1976) 'Self-planned learning and major personal change' reprinted in R. Edwards, S. Sieminski and D. Zeldin (eds.) (1993) Adult Learners, Education and Training, London: Routledge