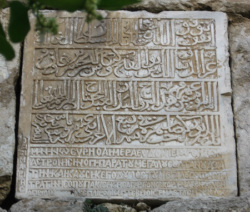

Sinop BILINGUAL inscription of Kaykaus I *

Sinop BILINGUAL inscription of Kaykaus I * Following recent discussion with a bilingual friend concerned about raising her five and two year-old daughters to acquire both languages (Greek and English) in a monolingual community, the issue of bilingualism and how this is best achieved in a foreign environment came to mind.

The question for new bilingual parents living in a monolingual country remains how to best help their offspring acquire both languages. Some are even justifiably concerned that one of the languages will soon be overshadowed by the majority language until it remains completely dormant. Others worry that their little ones will be mixing up both languages through incessant code switching, resulting thus in total confusion for the rest of their lives.

To tackle or prevent this in actual life, bilingual parents often have strict rules about their children using the minority language in the house and the majority one in social encounters and at school. Others adhere to the one parent-one language approach for as far as it takes. We should not rule out the cases of families who resort to using one language until elementary mastery and then switch to the second one after age three or four.

From discussions with friends, it appears that the second approach – as long as parents are prepared to stick to their linguistic choice – is what makes more sense to kids, as it allows them to clearly differentiate the two languages from an early age, thus preventing constant code switching as a form of linguistic fusion or even … confusion.

However, this may not necessarily be the case. This switching between languages may simply be a form of expressing social solidarity to establish rapport (or even to exclude others), it may signal the speaker’s attitude towards the listener (friendly, ironic, detached, jocular) or it may automatically come as a result of fatigue and distraction caused by linguistic inadequacy.

The process of learning two languages seems to differ from this of learning one and, usually by the fourth year, children become aware that the two languages are not the same.

During the first stage of development in the process of acquisition, bilingual children appear to mentally construct word lists of both languages. In the second stage, longer utterances contain words from both languages within a sentence but the amount of mixing is rapidly reduced. The third stage of bilingual acquisition is characterized by the development of ‘translation equivalents’. A common grammatical system is initially applied in both languages but in the fourth year, children are clearly aware of the differences between the languages and therefore choose to use each with the parent who speaks it. (D. Chrystal, 1987, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, CUP)

In a recent study (2004), Petitto and Dunbar point out that although early 'dual language exposure is most optimal to achieve highly proficient and dual language mastery, children arriving late to bilingual context can and do achieve language competence in their new language. Full mastery of the new language needs to occur in highly systematic and multiple contexts that are richly varied involving both home and community and, remarkably, cannot be achieved through classroom instruction alone'. Childhood bilingualism, as they remark, 'is frequently not balanced and simultaneous but the age of the first bilingual language exposure impacts children's ability to achieve linguistic fluency in the later-exposed language' ( http://adelanteschool.org/Peitto.pdf).

But why insist on ‘bilingual’ upbringing so much?

Newest research from Gage, F. and Battro suggests that “The brain is plastic and it can change as a result of experience” while Petitto (2003) points out that bilingualism makes your brain better though it requires more cognitive load initially. Children exposed to two languages from birth indeed experience cognitive advantages as they become more skillful 'multi-taskers' as compared to monolinguals (Petitto & Dunbar http://adelanteschool.org/Peitto.pdf)

There has also been a recent paradigm shift from old theory suggesting that second language learning was stored in a different part of the brain. Now it has been ascertained that L-2 is stored in the traditional areas of the brain for language including the Brocas area.http://faculty.coloradomtn.edu/blog/2009/07/tesol-2009-brain-based-language.html

Although studies on bilingualism are abundant, cognitive processes and neural foundations of language switching have received less attention.

Still, it is common knowledge that language “networking” and “mapping” subconsciously develop in the brain both prenatally and in early infancy. We all seem to be “wired” differently as human brains are very diverse and our individual learning experiences vary considerably.

So, whatever the choices parents make depending on their own unique circumstances, they need to be aware that bilinguals, being more experienced linguistically and also cognitively, can perform better in terms of focusing attention, while second and foreign language speakers find it more strainful to perform similar linguistic tasks.

On the basis of recent behavioural, neuroimaging and brain stimulation studies, foreign language learning and usage impose a cognitive load as they involve more neural areas and therefore multifaceted efforts such as analyzing, synthesizing, decision making, prioritising, activating previous knowledge, memorizing, making associations, sustaining attention, just to mention a few.

In her research, Dr Janet Zadina (http://pubs.cde.ca.gov/tcsii/video/Zadina1.asx) also suggests that the transition from thinking to learning involves a continuous process of repeatedly “firing” pathways in the brain. She also suggests that these efforts should be rigorous, meaningful, relevant with spiralling exposure to the target language, gradually expanding on the basis of children’s pragmatic knowledge and schemata (the scaffolding technique). This constant, meaningful and therefore stress-free exposure can lead to “wiring” and creating neural networks to establish viable learning habits for life.

And what are the implications for language teachers?

The implications of this new perspective of language education from the standpoint of Cognitive Neuroscience are manifold affecting teaching methods, instructional materials and approaches to learning.

As our aim as language teachers is to reach all ages and types of learners (auditory, visual, tactile/ kinaesthetic), we may gain insight into the learning process and the ways to improve teaching practices from neuroscience research. Although ‘our notions are still very primitive’, as neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran remarks, (Horgan 2009 in NYTESOLhttp://idiom.nystesol.org/articles/vol39-01.html), Dr Zadina suggests guiding learners to ‘benefit from varied approaches and build connections to existing knowledge’ on the basis of ‘The Multiple Pathways Model” implicated in learning. Therefore, learners need to be encouraged to take up an active pleasurable role in class in order to assimilate the language as in bilingual contexts and natural situations, by activating their knowledge of the world, their emotions, interests, social perception, visualisation & exploration skills,critical thinking, attention span and experience. Dr. Joyce Nutta’s demonstration video (http://www.brainresearch.us/ESLvideo) offers an example of how these pathways can be incorporated in a language lesson to enhance learning.

This linkage between neuroscience and education, with its subsequent research, may be new and it may call for further investigation on educational strategies to activate the Multiple Pathways Model but it may also come as confirmation of the tenets of existing Approaches in Language Learning and Acquisition. But then again this could be the topic of a completely new Post (and further research).

* (Picture released into public domain by Aramgar on commons.wikimedia.com)